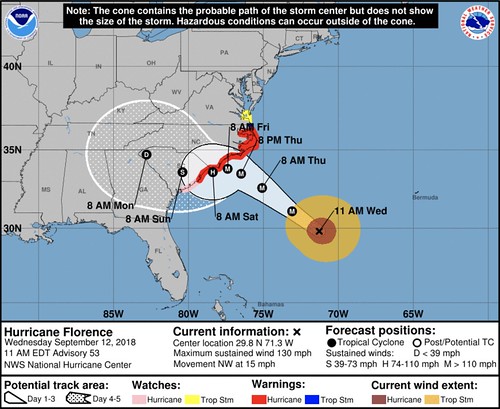

The big news this morning is the continued shift to the south on the official forecast track from the National Hurricane Center.

I know a lot of people are upset or confused about what is happening. So I wanted ot shed some light on the reasoning, hopefully explaining the why will help lower the agitation due to the change, and ultimately answer what it means for people living along the East Coast.

Here is what happened…

Turns out that the steering currents are breaking down while Florence moves toward the coast. This is something that forecast just couldn’t see coming. And we are lucky to have some many avenues for collecting data – between the Hurricane Hunters in the storm, planes flying around the perimeter of the storm, satellites in orbit, etc – that meteorologists picked up on this shift so early. Twenty years ago, meteorologists would’ve just watched this for another 48 hours before picking up on the change.

The new tech is also the reason why saying, “Well, they messed up forecasting XXX hurricane in 1990, so they don’t know what they are talking about.” is ridiculous. That a lot like saying that doctors, “didn’t know smoking caused cancer, so I won’t listen to them when they tell me not to eat paint chips.”

The Why Factor:

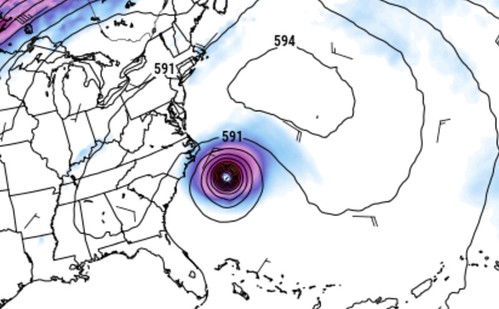

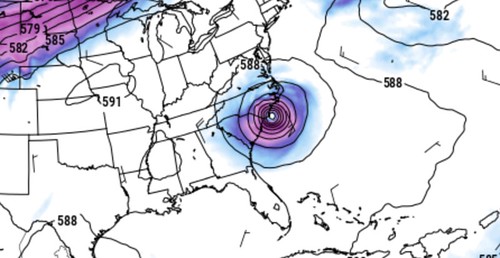

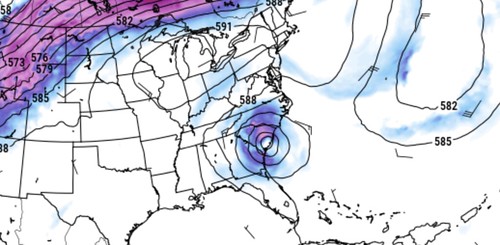

A big ridge of high pressure in the Atlantic has roped out a bit and poked its elbow along the east coast. That will nudge Florence to the south a bit as it approaches the coast. But as that ridge falls apart, a new ridge of high pressure is going to be moving across the midwest and northeast. As that moves in, the steering flow will shove Florence to the south a bit.

Here it is illustrated by the GFS from Pivotal Weather…

Notice the lines (isobars) on the map show that Florence runs into the ridge. It splits. The lingering parts are located over Mississippi and Iowa/Missouri. Then another ridge builds in across the Great Lakes and Northeast.

Forecasting storm motion in a situation like this becomes very difficult for models to do this far out. Models are okay with tropical system motion in low-steering-flow environments up to about 36 hours out.

Think of it like out summer time storms in the south. We can’t really tell you exactly where a thunderstorm will go more than about 12 hours out. Because a hurricane is massive, the models can do a bit better – but not great.

What does it mean?

Since we know that when steering currents breakdown, forecasting the storm track gets very tricky for forecast models, all model data with spot forecasts are nearly worthless at this point. Know that model data suggesting for forecast track is going to get iraditc and less predictable between Friday morning and Sunday morning in the short term (between now and Thursday morning). So, for now, if you see people posting model data with a specific landfall point, take it with a HUGE grain of salt.

Instead, trust the National Hurricane Center meteorologists forecast. It won’t be as specific, but it will be more accurate. It will take into account the unknowns and offer a solution that is more realistic given the current available data. This means more people will be on alert for storm impacts in the short-term. But the longer-term means more people will be prepared once the model data starts to come back with better data.

Who needs to change preparedness plans?

Not much has changed from the messaging side of things on this website if you’ve been following along. Folks from Jacksonville, FL north to Norfolk, VA need to be on alert for – at least – the next 24 hours while the NHC gets a better idea about where Florence will go.

Because the concerns with this hurricane involve the regular rain and wind, sure. But the specific track could mean incredible storm surge (up to 9ft above ground level in many places) along a wide stretch of the Georgia, the Carolinas and Virginia coasts. We may also see up to 40 inches of rain – with catastrophic flooding – occur in some areas in Georgia and the Carolinas.

Give me an example, here, Nick…

You got it. The forecast right now, shows it making landfall somewhere between Charleston, SC and Wilmington, NC. Let’s take the two extremes…

If landfall is in Charleston, the entire coastline from there north to Norfolk sees a Storm Surge and inland flooding of up to nine feet above ground level in some places – probably higher. Flooding from the rain inland causes problems across most of North Carolina and parts of South Carolina. The tornado threat would include most of North Carolina.

If landfall is in Wilmington, take all of the problems I just mentioned and shift them north about 100 miles. Norfolk would like have part of the downtown area under water. The Outer Banks would likely be wiped clean in many places. Rainfall and tornadoes would be a problem for southern Virginia (as far north as Richmond).

You can see how – from a preparedness messaging standpoint – this can become a headache for forecasters to warn people.

It is important for everyone to assess their own personal situation and make the right decision for themselves. My only advice is, if you live in the Carolinas within 10 miles of the ocean or 3 miles of any waterway, you really – really! – take a long look at your house and neighborhood. Take pictures. Make mental notes.

Given what I’ve been told by people who lived through Katrina and Harvey. It may never look the same again.

Okay, I’m in the path, what should I do?

I can’t tell you what to do, but I can recommend you check out the FEMA website for more information. Head here: https://www.fema.gov/hurricane-florence for more helpful information for making a decision about to stay or go.

I wish you could have seen the beauty and history of the coast before Katrina